Utilizator:Paloi Sciurala/Articole în lucru

|

|

Această pagină este o pagină unde dezvolt articole. |

| Eroare în script: Nu există modulul „Automated taxobox”. | |

|---|---|

| |

| Indian jungle cat | |

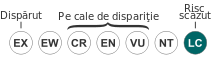

| Stare de conservare | |

| Clasificare științifică | |

| Specie: | Eroare în script: Nu există modulul „Autotaxobox”.Format:Taxon italics |

| Nume binomial | |

| Eroare în script: Nu există modulul „Autotaxobox”.Format:Taxon italics Schreber, 1777 | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| |

| Distribution of the jungle cat in 2016[1] | |

| Sinonime[2] | |

|

Listă Felis catolynx Pallas, 1811 F. erythrotus Hodgson, 1836 F. rüppelii von Brandt, 1832 F. jacquemontii Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, 1844 F. shawiana Blanford, 1876 Lynx chrysomelanotis (Nehring, 1902) | |

| Modifică text |

|

Pisica de junglă Pisica de stuf și mai era și de verificat The jungle cat (Felis chaus), also called reed cat and swamp cat, is a medium-sized cat native from the Eastern Mediterranean region and the Caucasus to parts of Central, South and Southeast Asia. It inhabits foremost wetlands like swamps, littoral and riparian areas with dense vegetation. It is listed as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List, and is mainly threatened by destruction of wetlands, trapping and poisoning.

The jungle cat has a uniformly sandy, reddish-brown or grey fur without spots; melanistic and albino individuals are also known. It is solitary in nature, except during the mating season and mother-kitten families.

Adults maintain territories by urine spraying and scent marking. Its preferred prey is small mammals and birds. It hunts by stalking its prey, followed by a sprint or a leap; the ears help in pinpointing the location of prey. Both sexes become sexually mature by the time they are one year old; females enter oestrus from January to March. Mating behaviour is similar to that in the domestic cat: the male pursues the female in oestrus, seizes her by the nape of her neck and mounts her. Gestation lasts nearly two months. Births take place between December and June, though this might vary geographically. Kittens begin to catch their own prey at around six months and leave the mother after eight or nine months.

The species was first described by Johann Anton Güldenstädt in 1776 based on a specimen caught in a Caucasian wetland. Johann Christian Daniel von Schreber gave the jungle cat its present binomial name and is therefore generally considered as binomial authority. Three subspecies are recognised at present.

Taxonomy and phylogeny

modificareTaxonomic history

modificareThe Baltic-German naturalist Johann Anton Güldenstädt was the first scientist who caught a jungle cat near the Terek River at the southern frontier of the Russian empire, a region that he explored in 1768–1775 on behalf of Catherine II of Russia.[3] He described this specimen in 1776 under the name "Chaus".[4][5]

In 1778, Johann Christian Daniel von Schreber used chaus as the species name and is therefore considered the binomial authority.[2][6] Paul Matschie in 1912 and Joel Asaph Allen in 1920 challenged the validity of Güldenstädt's nomenclature, arguing that the name Felis auriculis apice nigro barbatis was not a binomen and therefore improper, and that "chaus" was used as a common name rather than as part of the scientific name.[7]

In the 1820s, Eduard Rüppell collected a female jungle cat near Lake Manzala in the Nile Delta.[8] Thomas Hardwicke's collection of illustrations of Indian wildlife comprises the first drawing of an Indian jungle cat, named the "allied cat" (Felis affinis) by John Edward Gray in 1830.[9] Two years later, Johann Friedrich von Brandt proposed a new species under the name Felis rüppelii, recognising the distinctness of the Egyptian jungle cat.[10] The same year, a stuffed cat was presented at a meeting of the Asiatic Society of Bengal that had been caught in the jungles of Midnapore in West Bengal, India. J. T. Pearson, who donated the specimen, proposed the name Felis kutas, noting that it differed in colouration from Felis chaus.[11] Isidore Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire described a jungle cat from the area of Dehra Dun in northern India in 1844 under the name Felis jacquemontii in memory of Victor Jacquemont.[12]

In 1836, Brian Houghton Hodgson proclaimed the red-eared cat commonly found in Nepal to be a lynx and therefore named it Lynchus erythrotus;[13] Edward Frederick Kelaart described the first jungle cat skin from Sri Lanka in 1852 and stressed upon its close resemblance to Hodgson's red cat.[14] William Thomas Blanford pointed out the lynx-like appearance of cat skins and skulls from the plains around Yarkant County and Kashgar when he described Felis shawiana in 1876.[15]

Nikolai Severtzov proposed the generic name Catolynx in 1858,[16] followed by Leopold Fitzinger's suggestion to call it Chaus catolynx in 1869.[17] In 1898, William Edward de Winton proposed to subordinate the specimens from the Caucasus, Persia and Turkestan to Felis chaus typica, and regrouped the lighter built specimens from the Indian subcontinent to F. c. affinis. He renamed the Egyptian jungle cat as F. c. nilotica because Felis rüppelii was already applied to a different cat. A skin collected near Jericho in 1864 led him to describe a new subspecies, F. c. furax, as this skin was smaller than other Egyptian jungle cat skins.[18] A few years later, Alfred Nehring also described a jungle cat skin collected in Palestine, which he named Lynx chrysomelanotis.[19] Reginald Innes Pocock reviewed the nomenclature of felids in 1917 and classified the jungle cat group as part of the genus Felis.[20] Another subspecies, Felis chaus fulvidina, was named by Oldfield Thomas in 1928.[21]

During an expedition to Afghanistan in the 1880s, mammal skins were collected and later presented to the Indian Museum. One cat skin without a skull from the area of Maimanah in the country's north was initially identified as of Felis caudata, but in the absence of skins for comparison the author was not sure whether his identification was correct.[22] In his revision of Asiatic wildcat skins collected in the Zoological Museum of Berlin, the German zoologist Zukowsky reassessed the Maimanah cat skin, and because of its larger size and shorter tail than caudata skins proposed a new species with the scientific name Felis (Felis) maimanah. Zukowsky assumed that the cat inhabits the region south of the Amu Darya River.[23] The Russian zoologist Ognev acknowledged Zukowsky's assessment but also suggested that more material is needed for a definite taxonomic classification of this cat.[24] In his posthumously published monograph about skins and skulls of the genus Felis in the collection of the Natural History Museum, the British taxonomist Pocock referred neither to Zukowsky's appraisal nor to jungle cat skins from Afghanistan.[25] The British natural historian Ellerman and zoologist Morrison-Scott tentatively subordinated the Maimanah cat skin as a subspecies of Felis chaus.[26]

In 1969, the Russian biologist Heptner described a jungle cat from the lower course of the Vakhsh River in Central Asia and proposed the name Felis (Felis) chaus oxiana.[27]

In the 1930s, Pocock reviewed the jungle cat skins and skulls from British India and adjacent countries. Based mainly on differences in fur length and colour he subordinated the zoological specimens from Turkestan to Balochistan to F. c. chaus, the Himalayan ones to F. c. affinis, the ones from Cutch to Bengal under F. c. kutas, and the tawnier ones from Burma under F. c. fulvidina. He newly described six larger skins from Sind as F. c. prateri, and skins with shorter coats from Sri Lanka and southern India as F. c. kelaarti.[28]

Classification

modificareIn 2005, the authors of Mammal Species of the World recognized 10 subspecies as valid taxa.[2] Since 2017, the Cat Specialist Group considers only three subspecies as valid. Geographical variation of the jungle cat is not yet well understood and needs to be examined.[29] The following table is based on the classification of the species provided in Mammal Species of the World. It also shows the synonyms used in the revision of the Cat Classification Task Force:

| Subspecies | Synonymous with | Distribution |

|---|---|---|

| Felis chaus chaus Schreber, 1777 |

|

Caucasus, Turkestan, Iran, Baluchistan and Yarkand, East Turkestan, Palestine, Israel, southern Syria, Iraq, Egypt;[30] northern Afghanistan and south of the Amu Darya River;[31] along the right tributaries of the Amu Darya River, in the lower courses of the Vakhsh River ranging eastwards to the Gissar Valley and slightly beyond Dushanbe.[27] |

| Felis chaus affinis Gray, 1830 |

|

South Asia: Himalayan region ranging from Kashmir and Nepal to Sikkim, Bengal westwards to Kutch and Yunnan, southern India and Sri Lanka[30] |

| Felis chaus fulvidina Thomas, 1929 | Southeast Asia: ranging from Myanmar and Thailand to Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam[30] |

Phylogeny

modificareIn 2006, the phylogenetic relationship of the jungle cat was described as follows:[32][33]

| Felinae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The jungle cat is a member of the genus Felis within the family Felidae.[2]

Results of an mtDNA analysis of 55 jungle cats from various biogeographic zones in India indicate a high genetic variation and a relatively low differentiation between populations. It appears that the central Indian F. c. kutas population separates the Thar Desert F. c. prateri populations from the rest and also the south Indian F. c. kelaarti populations from the north Indian F. c. affinis ones. The central Indian populations are genetically closer to the southern than to the northern populations.[34]

Characteristics

modificareThe jungle cat is a medium-sized, long-legged cat, and the largest of the extant Felis species.[35][36] The head-and-body length is typically between 59 și 76 cm (23 și 30 in). It stands nearly 36 cm (14 in) at shoulder and weighs 2–16 kg (4,4–35,3 lb).[37][38] Its body size decreases from west to east; this was attributed to greater competition from small cats in the east.[39] Its body size shows a similar decrease from the northern latitudes toward the tropics. Sexually dimorphic, females tend to be smaller and lighter than males. The face is long and narrow, with a white muzzle. The large, pointed ears, 4,5–8 cm (1,8–3,1 in)[Convert: Număr în engleză] in length and reddish brown on the back, are set close together; a small tuft of black hairs, nearly 15 mm (0,59 in) long, emerges from the tip of both ears. The eyes have yellow irises and elliptical pupils; white lines can be seen around the eye. Dark lines run from the corner of the eyes down the sides of the nose and a dark patch marks the nose.[37][38][40] The skull is fairly broad in the region of the zygomatic arch; hence the head of this cat appears relatively rounder.[27]

The coat, sandy, reddish brown or grey, is uniformly coloured and lacks spots; melanistic and albino individuals have been reported from the Indian subcontinent. White cats observed in the coastline tracts of the southern Western Ghats lacked the red eyes typical of true albinos. A 2014 study suggested that their colouration could be attributed to inbreeding.[41] Kittens are striped and spotted, and adults may retain some of the markings. Dark-tipped hairs cover the body, giving the cat a speckled appearance. The belly is generally lighter than the rest of the body and the throat is pale. The fur is denser on the back compared to the underparts. Two moults can be observed in a year; the coat is rougher and lighter in summer than in winter. The insides of the forelegs show four to five rings; faint markings may be seen on the outside. The black-tipped tail, 21 la 36 cm (8,3 la 14,2 in) long, is marked by two to three dark rings on the last third of the length.[38][35] The pawprints measure about 5 × 6 cm (2,0 × 2,4 in); the cat can cover 29 la 32 cm (11 la 13 in) in one step.[27] There is a distinct spinal crest.[40] Because of its long legs, short tail and tuft on the ears, the jungle cat resembles a small lynx.[35] It is larger and more slender than the domestic cat.[42]

Distribution and habitat

modificareThe jungle cat is found in the Middle East, the Caucasus, the Indian subcontinent, central and Southeast Asia, Sri Lanka and in southern China.[1][43][40] A habitat generalist, the jungle cat inhabits places with adequate water and dense vegetation, such as swamps, wetlands, littoral and riparian areas, grasslands and shrub. It is common in agricultural lands, such as fields of bean and sugarcane, across its range, and has often been sighted near human settlements. As reeds and tall grasses are typical of its habitat, it is known as "reed cat" or "swamp cat".[44][42] It can thrive even in areas of sparse vegetation, but does not adapt well to cold climates and is rare in areas where snowfall is common.[35] Historical records indicate that it occurs up to elevations of 2.310 m (7.580 ft) in the Himalayas.[28] It shuns rainforests and woodlands.[35][36][42]

In Turkey, it has been recorded in wetlands near Manavgat, in the Akyatan Lagoon on the southern coast and near Lake Eğirdir.[45][46] In the Palestinian territories, it was recorded in the Nablus, Ramallah, Jericho and Jerusalem Governorates in the West Bank during surveys carried out between 2012 and 2016.[47]

In Iran, it inhabits a variety of habitat types from plains and agriculture lands to mountains ranging from elevations of 45 la 4.178 m (148 la 13.707 ft) in at least 23 of 31 provinces of Iran.[48] In Pakistan, it was photographed in Haripur, Dera Ismail Khan, Sialkot Districts and Langh Lake Wildlife Sanctuary.[49]

In India, it is the most common small wild cat.[39] In Nepal, it was recorded in alpine habitat at elevations of 3.000–3.300 m (9.800–10.800 ft) in Annapurna Conservation Area between 2014 and 2016.[50]

In Malaysia, it was recorded in a highly fragmented forest in the Selangor state in 2010.[51]

A few jungle cat mummies were found among the cats in ancient Egypt.[52][53][54]

Ecology and behaviour

modificareThe jungle cat is typically diurnal and hunts throughout the day. Its activity tends to decrease during the hot noon hours. It rests in burrows, grass thickets and scrubs. It often sunbathes on winter days. Jungle cats have been estimated to walk 3–6 km (1,9–3,7 mi) at night, although this likely varies depending on the availability of prey. The behaviour of the jungle cat has not been extensively studied. Solitary in nature, it does not associate with conspecifics, except in the mating season. The only prominent interaction is the mother-kitten bond. Territories are maintained by urine spraying and scent marking; some males have been observed rubbing their cheeks on objects to mark them.[38][35]

Leopards, tigers, bears, crocodiles, dholes, golden jackals, fishing cats, large raptors and snakes are the main predators of the jungle cat.[27][38] The golden jackal in particular can be a major competitor to jungle cats.[55] When it encounters a threat, the jungle cat will vocalise before engaging in attack, producing sounds like small roars – a behavior uncommon for the other members of Felis. The meow of the jungle cat is also somewhat lower than that of a typical domestic cat.[27][38] The jungle cat can host parasites such as Haemaphysalis ticks and Heterophyes trematode species.[56]

Diet and hunting

modificarePrimarily a carnivore, the jungle cat prefers small mammals such as gerbils, hares and rodents. It also hunts birds, fishes, frogs, insects and small snakes. Its prey typically weighs less than 1 kg (2,2 lb), but occasionally includes mammals as large as young gazelles.[38][35] The jungle cat is unusual in that it is partially omnivorous: it eats fruits, especially in winter. In a study carried out in Sariska Tiger Reserve, rodents were found to comprise as much as 95% of its diet.[57]

The jungle cat hunts by stalking its prey, followed by a sprint or a leap; the sharp ears help in pinpointing the location of prey. It uses different techniques to secure prey. The cat has been observed searching for musk rats in their holes. Like the caracal, the jungle cat can perform one or two high leaps into the air to grab birds.[35] It is an efficient climber as well.[27] The jungle cat has been clocked at 32 km/h (20 mph).[36][35] It is an efficient swimmer, and can swim up to 1,5 km (0,93 mi)[Convert: Număr în engleză] in water and plunge into water to catch fish.[58]

Reproduction

modificareBoth sexes become sexually mature by the time they are one year old. Females enter oestrus lasting for about five days, from January to March. In males, spermatogenesis occurs mainly in February and March. In southern Turkmenistan, mating occurs from January to early February. The mating season is marked by noisy fights among males for dominance. Mating behaviour is similar to that in the domestic cat: the male pursues the female in oestrus, seizes her by the nape of her neck and mounts her. Vocalisations and flehmen are prominent during courtship. After a successful copulation, the female gives out a loud cry and reacts with aversion towards her partner. The pair then separate.[27][38]

Gestation lasts nearly two months. Births take place between December and June, though this might vary geographically. Before parturition, the mother prepares a den of grass in an abandoned animal burrow, hollow tree or reed bed.[35] Litters comprise one to five kittens, typically two to three kittens. Females can raise two litters in a year.[27][38] Kittens weigh between 43 și 55 g (1,5 și 1,9 oz) at birth, tending to be much smaller in the wild than in captivity. Initially blind and helpless, they open their eyes at 10 to 13 days of age and are fully weaned by around three months. Males usually do not participate in the raising of kittens; however, in captivity, males appear to be very protective of their offspring. Kittens begin to catch their own prey at around six months and leave the mother after eight or nine months.[27][59] The lifespan of the jungle cat in captivity is 15 to 20 years; this is possibly higher than that in the wild.[38]

Generation length of the jungle cat is 5.2 years.[60]

Threats

modificareMajor threats to the jungle cat include habitat loss such as the destruction of wetlands, dam construction, environmental pollution, industrialisation and urbanisation. Illegal hunting is a threat in Turkey and Iran. Its rarity in Southeast Asia is possibly due to high levels of hunting.[1] Since the 1960s, populations of the Caucasian jungle cat living along the Caspian Sea and in the Caucasus range states have been rapidly declining. Only small populations persist today. There has been no record in the Astrakhan Nature Reserve in the Volga Delta since the 1980s.[61] It is rare in the Middle East. In Jordan, it is highly affected by the expansion of agricultural areas around the river beds of Yarmouk and Jordan rivers, where farmers hunted and poisoned jungle cats in retaliation for attacking poultry.[62] It is also considered rare and threatened in Afghanistan.[63] India exported jungle cat skins in large numbers, until this trade was banned in 1979; some illegal trade continues in the country, in Egypt and Afghanistan.[1]

In the 1970s, Southeast Asian jungle cats still used to be the most common wild cats near villages in certain parts of northern Thailand and occurred in many protected areas of the country.[64] However, since the early 1990s, jungle cats are rarely encountered and have suffered drastic declines due to hunting and habitat destruction. Today, their official status in the country is critically endangered.[65] In Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam, jungle cats have been subject to extensive hunting. Skins are occasionally recorded in border markets, and live individuals, possibly taken from Myanmar or Cambodia, occasionally turn up in the Khao Khieo and Chiang Mai zoos of Thailand.[66]

Conservation

modificareThe jungle cat is listed under CITES Appendix II. Hunting is prohibited in Bangladesh, China, India, Israel, Myanmar, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Thailand and Turkey. But it does not receive legal protection outside protected areas in Bhutan, Georgia, Laos, Lebanon, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Vietnam.[44]

References

modificare- ^ a b c d e f Gray, T.N.E.; Timmins, R.J.; Jathana, D.; Duckworth, J.W.; Baral, H.; Mukherjee, S. (). „Felis chaus”. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T8540A200639312. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-2.RLTS.T8540A200639312.en . Accesat în . Parametru necunoscut

|amends=ignorat (ajutor) - ^ a b c d Wozencraft, W. C. (). „Order Carnivora”. În Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. Mammal Species of the World (ed. 3rd). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 535. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Güldenstädt, J. A. (). Reisen durch Russland und im Caucasischen Gebürge (în germană). St. Petersburg, Russia: Kayserliche Akademie der Wissenschaften.

- ^ Güldenstädt, J. A. (). „Chaus – Animal feli adfine descriptum”. Novi Commentarii Academiae Scientiarum Imperialis Petropolitanae (în latină). 20: 483–500.

- ^ Sanderson, J. (). „A Matter of Very Little Moment? The mystery of who first described the jungle cat”. Feline Conservation Federation. 53 (1): 12–18.

- ^ Schreber, J. C. D. (). „Der Kirmyschak”. Die Säugethiere in Abbildungen nach der Natur, mit Beschreibungen. Erlangen: Wolfgang Walther. pp. 414–416.

- ^ Allen, J. A. (). „Note on Güldenstädt's names of certain species of Felidae”. Journal of Mammalogy. 1 (2): 90–91. doi:10.1093/jmammal/1.2.90.

- ^ Rüppell, E. (). „Felis chaus, der Kirmyschak”. Atlas zu der Reise im nördlichen Afrika (în germană). pp. 13–14.

- ^ Gray, J. E. (). Illustrations of Indian Zoology chiefly selected from the collection of Major-General Hardwicke. 1. London, UK: Treuttel, Wurtz, Treuttel, jun. and Richter.

- ^ Brandt, J. F. (). „De nova generis Felis specie, Felis Rüppelii nomine designanda hucusque vero cum Fele Chau confusa”. Bulletin de la Société Impériale des Naturalistes de Moscou (în latină). 4: 209–213.

- ^ Pearson, J. T. (). „A stuffed specimen of a species of Felis, native of the Midnapure jungles”. Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. 1: 75.

- ^ Saint-Hilaire, I. G. (). Voyage dans l'Inde, par Victor Jacquemont, pendant les années 1828 à 1832 [Travel in India, Victor Jacquemont, during the years 1828 to 1832] (în franceză). Paris, France: Firmin Didot Frères.

- ^ Hodgson, B. H. (). „Synoptical description of sundry new animals, enumerated in the Catalogue of Nepalese Mammals”. Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. 5: 231–238.

- ^ Kelaart, E. F. (). „Felis chaus”. Prodromus Faunæ Zeylanicæ: 48.

- ^ Blanford, W. T. (). „Description of Felis shawiana, a new Lyncine cat from eastern Turkestan”. The Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. 45 (2): 49–51.

- ^ Severtzov, N. (). „Notice sur la classification multisériale des Carnivores, spécialement des Félidés, et les études de zoologie générale qui s'y rattachent”. Revue et Magasin de Zoologie Pure et Appliquée (în franceză). 2: 385–396.

- ^ Fitzinger, L. (). „Revision der zur natürlichen Familie der Katzen (Feles) gehörigen Formen”. Sitzungsberichte der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftliche Classe der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften (în germană). 60 (1): 173–262.

- ^ de Winton, W. E. (). „Felis chaus and its allies, with descriptions of new subspecies”. The Annals and Magazine of Natural History: Including Zoology, Botany, and Geology. 2. 2 (10): 291–294. doi:10.1080/00222939808678046.

- ^ Nehring, A. (). „Über einen neuen Sumpfluchs (Lynx chrysomelanotis) aus Palästina”. Schriften der Berlinischen Gesellschaft Naturforschender Freunde (în germană). Jahrgang 6: 124–128.

- ^ Pocock, R. I. (). „Classification of existing Felidae”. The Annals and Magazine of Natural History: Including Zoology, Botany, and Geology. 8th. 20 (119): 329–350. doi:10.1080/00222931709487018.

- ^ Thomas, O. (). „The Delacour Exploration of French Indo-China.— Mammals. III. Mammals collected during the Winter of 1927–28”. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 98 (4): 831–841. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1928.tb07170.x.

- ^ Scully, J. (1887). On the mammals collected by Captain C. E. Yate, C.S.I., of the Afghan Boundary Commission. The Annals and Magazine of Natural History: Including Zoology, Botany, and Geology. Fifth Series, Vol. XX: 378–388.

- ^ Zukowsky, L. (). „Drei neue Kleinkatzenrassen aus Westasien: Felis (Felis) maimanah spec. nov.”. Archiv für Naturgeschichte. 80 (10): 139−142.

- ^ Ognev, S. I. (1935). Zveri SSSR i priležaščich stran. Tom III. Gosudarstvennoe izdatel'stvo biologičeskoj i medicinskoj literatury, Moskva i Leningrad. Page 144. (in Russian; Mammals of USSR and adjacent countries. Volume III.)

- ^ Pocock, R. I. (1951). Catalogue of the Genus Felis. The Trustees of the British Museum, London.

- ^ Ellerman, J. R.; Morrison-Scott, T. C. S. (). „Felis chaus Güldenstädt, 1776”. Checklist of Palaearctic and Indian mammals 1758 to 1946 (ed. Second). London: British Museum of Natural History. pp. 306–307.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Geptner, V. G.; Sludskij, A. A. () [1972]. „Jungle Cat”. Mlekopitajuščie Sovetskogo Soiuza. Moskva: Vysšaia Škola [Mammals of the Soviet Union. Volume II, Part 2. Carnivora (Hyaenas and Cats)]. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution and the National Science Foundation. pp. 356–398.

- ^ a b Pocock, R. I. (). The Fauna of British India, including Ceylon and Burma. Mammalia. 1. London: Taylor and Francis. pp. 290–305.

- ^ Kitchener, A.C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Eizirik, E.; Gentry, A.; Werdelin, L.; Wilting, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Abramov, A. V.; Christiansen, P.; Driscoll, C.; Duckworth, J. W.; Johnson, W.; Luo, S.-J.; Meijaard, E.; O’Donoghue, P.; Sanderson, J.; Seymour, K.; Bruford, M.; Groves, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Nowell, K.; Timmons, Z.; Tobe, S. (). „A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group” (PDF). Cat News. Special Issue 11: 11–13.

- ^ a b c Ellerman, J.R.; Morrison-Scott, T.C.S. (). „Felis chaus Güldenstädt 1776”. Checklist of Palaearctic and Indian Mammals 1758 to 1946 (ed. 2nd). London: British Museum of Natural History. pp. 306–307.

- ^ Zukowsky, L. (). „Drei neue Kleinkatzenrassen aus Westasien” [Three new small breeds from east Asia]. Archiv für Naturgeschichte (în germană). 80 (10): 139–142.

- ^ Johnson, W.E.; Eizirik, E.; Pecon-Slattery, J.; Murphy, W.J.; Antunes, A.; Teeling, E.; O'Brien, S.J. (). „The Late Miocene radiation of modern Felidae: A genetic assessment”. Science. 311 (5757): 73–77. Bibcode:2006Sci...311...73J. doi:10.1126/science.1122277. PMID 16400146.

- ^ Werdelin, L.; Yamaguchi, N.; Johnson, W.E.; O'Brien, S.J. (). „Phylogeny and evolution of cats (Felidae)”. În Macdonald, D.W.; Loveridge, A.J. Biology and Conservation of Wild Felids (ed. Reprint). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 59–82. ISBN 978-0-19-923445-5.

- ^ Mukherjee, S.; Krishnan, A.; Tamma, K.; Home, C.; R., N.; Joseph, S.; Das, A.; Ramakrishnan, U.; Murphy, W.J. (). „Ecology driving genetic variation: A comparative phylogeography of jungle cat (Felis chaus) and leopard cat (Prionailurus bengalensis) in India”. PLOS ONE. 5 (10): e13724. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...513724M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013724 . PMC 2966403 . PMID 21060831.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Sunquist, M.; Sunquist, F. (). „Jungle cat Felis chaus (Schreber, 1777)”. Wild Cats of the World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 60–66. ISBN 978-0-226-77999-7.

- ^ a b c Hunter, L. (). „Jungle Cat Felis chaus (Schreber, 1777)”. Wild Cats of the World. London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 38–41. ISBN 978-1-4729-2285-4.

- ^ a b Burnie, D.; Wilson, D.E., ed. (). Animal (ed. First American). New York: Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-0-7894-7764-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Glas, L. (). „Felis chaus Swamp Cat (Jungle Cat)”. În Kingdon, J.; Hoffmann, M. Mammals of Africa. ((V. Carnivores, Pangolins, Equids and Rhinoceroses)). London: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 197–199. ISBN 978-1-4081-8996-2.

- ^ a b Mukherjee, S.; Groves, C. (). „Geographic variation in jungle cat (Felis chaus Schreber, 1777) (Mammalia, Carnivora, Felidae) body size: is competition responsible?”. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 92 (1): 163–172. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2007.00838.x .

- ^ a b c Wozencraft, W.C. (). „Jungle cat Felis chaus (Schreber, 1777)”. În Smith, A.T.; Xie, Y. A Guide to the Mammals of China. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 394. ISBN 978-1-4008-3411-2.

- ^ Sanil, R.; Shameer, T.T.; Easa, P.S. (). „Albinism in jungle cat and jackal along the coastline of the southern Western Ghats”. Cat News (61): 23–25.

- ^ a b c Sunquist, F.; Sunquist, M. (). The Wild Cat Book: Everything You Ever Wanted to Know about Cats. Chicago, USA: University of Chicago Press. pp. 239–241. ISBN 978-0-226-78026-9.

- ^ Blanford, W.T. (). „Felis chaus”. The Fauna of British India, including Ceylon and Burma. London: Taylor & Francis. pp. 86–88.

- ^ a b Nowell, K.; Jackson, P. (). „Jungle cat Felis chaus”. Wild Cats: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. IUCN Species Survival Commission Cat Specialist Group. Arhivat din original la .

- ^ Avgan, B. (). „Sighting of a jungle cat and the threats of its habitat in Turkey”. Cat News. 50: 16.

- ^ Ogurlu, I.; Gundogdu, E.; Yildirim, I. C. (). „Population status of jungle cat (Felis chaus) in Egirdir lake, Turkey”. Journal of Environmental Biology. 31 (31): 179−183. PMID 20648830.

- ^ Albaba, I. (). „The terrestrial mammals of Palestine: A preliminary checklist”. International Journal of Fauna and Biological Studies. 3 (4): 28−35.

- ^ Sanei, A.; Mousavi, M.; Rabiee, K.; Khosravi, M. S.; Julaee, L.; Gudarzi, F.; Jaafari, B.; Chalani, M. (). „Distribution, characteristics and conservation of the jungle cat in Iran”. Cat News. Special Issue 10: 51–55.

- ^ Anjum, A.; Appel, A.; Kabir, M. (). „First photographic record of Jungle Cat Felis chaus Schreber, 1777 (Mammalia: Carnivora: Felidae) in Haripur District, Pakistan”. Journal of Threatened Taxa. 12 (2): 15251–15255. doi:10.11609/jott.5386.12.2.15251-15255 .

- ^ Shrestha, B.; Subedi, N.; Kandel,R. C. (). „Jungle Cat Felis chaus Schreber, 1777 (Mammalia: Carnivora: Felidae) at high elevations in Annapurna Conservation Area, Nepal”. Journal of Threatened Taxa. 12 (2): 15267–15271. doi:10.11609/jott.5580.12.2.15267-15271 .

- ^ Sanei, A.; Zakaria, M. (). „Possible first jungle cat record from Malaysia”. Cat News. 53: 13–14.

- ^ Morrison-Scott, T. C. S. (). „The mummified cats of ancient Egypt” (PDF). Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 121 (4): 861–867. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1952.tb00788.x.

- ^ Linseele, V.; Van Neer, W.; Hendrickx, S. (). „Early cat taming in Egypt”. Journal of Archaeological Science. 35 (9): 2672–2673. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2008.04.009.

- ^ Hanzak, J. (). „Egyptian Mummies of Animals in Czechoslovak Collections”. Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde. 104 (1): 86–88. doi:10.1524/zaes.1977.104.jg.86.

- ^ Majumder, A.; Sankar, K.; Qureshi, Q.; Basu, S. (). „Food habits and temporal activity patterns of the golden jackal Canis aureus and the jungle cat Felis chaus in Pench Tiger Reserve, Madhya Pradesh”. Journal of Threatened Taxa. 3 (11): 2221–2225. doi:10.11609/JoTT.o2713.2221-5 .

- ^ Hoogstraal, H.; Trapido, H. (). „Haemaphysalis silvafelis sp. n., a parasite of the jungle cat in southern India (Ixodoidea, Ixodidae)”. The Journal of Parasitology. 49 (2): 346–349. doi:10.2307/3276012. JSTOR 3276012.

- ^ Mukherjee, S.; Goyal, S.P.; Johnsingh, A.J.T.; Pitman, M.R.P.L. (). „The importance of rodents in the diet of jungle cat (Felis chaus), caracal (Caracal caracal) and golden jackal (Canis aureus) in Sariska Tiger Reserve, Rajasthan, India”. Journal of Zoology. 262 (4): 405–411. doi:10.1017/S0952836903004783.

- ^ Hinde, G.; Hunter, L. (). Cats of Africa: Behaviour, Ecology, and Conservation. Cape Town, South Africa: Struik Publishers. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-77007-063-9.

- ^ Schauenberg, P. (). „La reproduction du Chat des marais Felis chaus (Güldenstädt, 1776)” [Reproduction of swamp cat Felis chaus (Güldenstädt, 1776)]. Mammalia (în franceză). 43 (2): 215–223. doi:10.1515/mamm.1979.43.2.215.

- ^ Pacifici, M.; Santini, L.; Di Marco, M.; Baisero, D.; Francucci, L.; Grottolo Marasini, G.; Visconti, P.; Rondinini, C. (). „Generation length for mammals”. Nature Conservation (5): 87–94.

- ^ Prisazhnyuk, B. E.; Belousova, A. E. (). Красная Книга России: Кавкаэский Камышовый Кот Felis chaus (подвид chaus) (în rusă). Accesat în .

- ^ Abu-Baker, M.; Nassar, K.; Rifai, L.; Qarqaz, M.; Al-Melhim, W.; Amr, Z. (). „On the current status and distribution of the Jungle Cat, Felis chaus, in Jordan (Mammalia: Carnivora)” (PDF). Zoology in the Middle East. 30: 5–10. doi:10.1080/09397140.2003.10637982.

- ^ Habibi, K. (). „Jungle Cat Felis chaus”. Mammals of Afghanistan. Coimbatore, India: Zoo Outreach Organisation. ISBN 9788188722068.

- ^ Lekagul, B., McNeely, J.A. (1988). Mammals of Thailand. 2nd ed. Saha Karn Bhaet, Bangkok.

- ^ Lynam, A.J., Round, P., Brockelman, W.Y. (2006). Status of birds and large mammals of the Dong Phayayen-Khao Yai Forest Complex, Thailand. Biodiversity Research and Training Program and Wildlife Conservation Society, Bangkok, Thailand.

- ^ Duckworth, J. W.; Poole, C. M.; Tizard, R. J.; Walston, J. L.; Timmins, R. J. (). „The Jungle Cat Felis chaus in Indochina: a threatened population of a widespread and adaptable species”. Biodiversity & Conservation. 14 (5): 1263–1280. doi:10.1007/s10531-004-1653-4.

External links

modificare- Materiale media legate de Paloi Sciurala/Articole în lucru la Wikimedia Commons

Category:Felis Category:Mammals described in 1777 Category:Felids of Europe Category:Mammals of Europe Category:Mammals of the Middle East Category:Mammals of Central Asia Category:Mammals of West Asia Category:Mammals of South Asia Category:Mammals of Southeast Asia Category:Taxa named by Johann Christian Daniel von Schreber